Growing Up With Hulk – By David Maber

David Maber – tells the story of ‘C1’

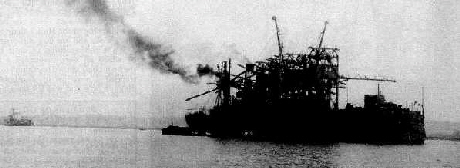

A ‘floating coalyard’ Hulk that served the Navy for 60 years.

It was black, longer than a football pitch and about 100 feet high. It was ugly and it had been squatting in the one place for some years when I first glimpsed it in 1931. During my formative years I saw it daily. It was once instrumental in showering my body with red hot cinders. Another time it had me suspended by my thumb. yet it provided me with some tasty meals.

The ‘Coal Hulk”, as she was referred to locally, was an unnamed static floating marine equivalent of a landlubber’s coal-yard. Moored in Portsmouth Harbour and recognised officially as the Cl, she supplied solid fuel to the, now extinct, coal-burning tugs and battleships for more than half a century.

Move to Hardway

My family moved to Hardway — a parish on the harbour side of the Gosport peninsula — in 1931, and already in place, about 300 yards offshore from our sea-edge garden, was the Coat Hulk. A smoldering leviathan tethered by gigantic chains to the sea-bed. Its bulk dominated the centre of my family’s I80º vista of the harbour.

During the days of my youth I did not feel compelled to enquire of her pedigree; it is only in retirement that I have felt a need to find out more about her and to share the information. Research revealed construction of the Cl commenced as an Admiralty contract job in 1901. The hull was launched from the Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson Yard on February 27, 1902. Work continued aboard while she was afloat, and, at the same time her cranes were constructed in the nearby Yard. Completion was effected in June 1904.

With dismantled cranes stowed within her hull she left the Tyne on June 23, 1904 and commenced her three day east, south coast journey under tow, to Portsmouth. The work of assembling the wheeled cranes, locating them on the deck rails and generally making the vessel ready was undertaken in Portsmouth Dockyard. She was ready by October 1904, when she was put into service on a mooring close by Portsmouth Dockyard.

In the ‘20s she was moved up harbour to be moored close to Hardway, where she was to complete her 60 years of service, I often observed The Hulk’ at close quarters, when, as a child, my parents would usher my brothers and sisters into the family dinghy, then row past it on a tour of the harbour.

Colliers laying low in the water regularly tied up alongside to discharge hundreds of tons of Welsh Steam Coal into its cavernous hull. Spilled coal tempted passing boatmen to collect it from projecting ribs along the hull side. Those in the know ignored it having already found it unsuitable fuel for use on a domestic open fire.

The refuelling of visiting ships was a noisy affair. The Hulk had four rail-mounted cranes with booms that pointed skyward when idle and horizontal when about to transfer to, or take in coal from, vessels alongside. I would frequently watch as giant coal-filled steel buckets, large enough to accommodate ten men standing, would be wrenched upwards by cable from the Hulk’s belly passing through clouds of airborne dust.

Metal cable-controlled trolleys would convey the suspended bucket along the outstretched boom. As it did so the metal on metal squealed like pigs at the trough. The trolley would finally jolt to a stop, the loaded bucket would swing, then be allowed to steady, A small adjusting movement placed it immediately over the customer ship’s hold and the bucket would descend. Responsibility for the dangerous job of releasing the ratchet that allowed the full bucket to upturn and spill its contents, lay with the crew of the ship being loaded.

The crane drivers, part of an overall crew shrinking in number since the 30s, appeared to operate the bucket in a devil-may-care manner when coal was destined for a large ship’s hold, however their true expertise would be evident when directing a full bucket carefully and precisely towards the deck of smaller vessels such as tugs.

I grew up with the Coal Hulk, alias the ‘C.1.’ rather as many children might grow up with a nearby corner shop She was frequently included in the background of family snaps taken in our garden. It was though we were wishing to include a friend of the family. She was always there, a ‘living’ thing puffing steam and belching smoke from her single stack. While she possessed a steam-driven generator, at some point in time, electrical energy for her working | parts was laid on by way of a submarine cable extended from the mainland.

Fishing by the Hulk

Trailing from the submerged part of the Hulk’s hull was a veritable forest of seaweed attracting Bass and Mullet to it. This prompted myself and many other locals to cast a fishing line, ever hopefully, alongside. Despite being ‘electrified’, the C.l. continued to burn freely available solid fuel in an onboard boiler. I found to my cost that boiler cleaning meant the dumping of unwanted burnt and burning cinders over the vessel’s side, from a giant bucket. Stripped to the waist and fishing from a dingy alongside the Hulk, I, a friend and my dog once suffered the consequences of this practice. ‘ Without any warning’ dust ash and red-hot cinders arrived in one large lump, scorching the heads, shoulders and legs of both my friend and I. At the same time a strange smell signalled my dog’s coat was burning. Fortunately, the action of throwing the dog overboard then following him into the water saved all from serious burns. It only remained for us to upturn and flood the burning dinghy as it took on the appearance of a Viking funeral boat.

A subsequent fishing trip had us more cautious. We lashed the dinghy’s painter to the Hulk’s anchor chain, an arrangement that kept us well away from her hull and the dangers of raining embers. A tide change and the consequent rapid straightening of the Hulk’s chain rendered boat, selves and one dog, airborne. While endeavouring to untie the rope by which all were suspended a lurch in the huge chain caused my thumb to become trapped. I next lost my foothold on the dinghy’s bow and was left hanging by the trapped thumb. When my fishing partner finally cut through the rope we were all treated to yet another salty dunking. Patiently treading water and wearing a ‘not again’ expression, my dog was last to clamber back into the waterlogged dinghy as our catch of fish drifted down-harbour.

My opening remarks termed the C.1. ugly, I could have added passive and impotent, since she was unable to move under her own power, relying instead on tugs.

Passive would not describe the conduct of the French battleship Courbay’s crew, taken over by the British Navy, impounded and moored a couple of hundred yards away from the C.1. in July 1940. The Courbay bristled with fixed guns; it also boasted many hand-held weapons. Unfortunately for the residents of Hardway and crew of the C.1., the French crew were permitted to use these weapons during air-raids; and they did so, with gusto. My family’s shoreside air-raid shelter was located opposite the Courbay, and I well recall that during air-raids the French crew would sometimes spray the area with bullets — and the occasional shell. As dawn broke after a raid, we would vacate the dubious safety of our shelter and check to see if the C.1. was still afloat, since it had been exposed to the double hazard of German and French attack.

The C.1. survived two World Wars, although due to the then wider use of coal as a fuel, was infinitely more busy during the 1914 to 1918 conflict.. After the Second World War she was moved to the Dockyard for a refit — her last. She spent the Last quarter of 1946 in Dry Dock before being returned to her moorings off Hardway,

Phasing Out of Coal as a Marine Fuel

Inevitably, with the phasing out of coal as a marine fuel, she drifted into redundancy. The profile of the moored C.1. or Coal Hulk, largest coaling vessel in the world, was seen to change in the late ’50s when most of her superstructure and two of her cranes were dismantled. Her fate was sealed when her owners, the Admiralty, sold her to a Dutch firm of breakers.

Sixty years of service ended when the giant black hulk left Portsmouth harbour. But for records at The National Maritime Museum I would not have been able to date her departure, noted by them as, January 16, 1964, I find it incredible that a ‘shipping movement of this magnitude did not justify a photograph or mention in the local newspaper of the day. On the other hand — the old girl really was quite ugly.

Information supplied by: Swan Hunter Ltd

DESIGN – The Cl was unique. The first of its type in the world,

CONTRACT Number 290.

PROFIT ON CONTRACT – £5.864 4s. 8d,

DIMENSIONS – L. 424′ x B. 67’8 3/8’’ D.M. 40′

CREW ACCOMMODATION – Designed for SO crew.

LOADING ARRANGEMENTS – 11,000 tons of coaI in hoppers. 1.080 tons in bags.

HULL – Large barn type construction subdivided into seven holds.

HOPPERS – Fitted with 80 coal chutes for filling bags without the use of shovels.

TRANSPORTERS – Equipped with 12 Temperly electric transporters.

LAUNCHED – February 27, 1902.

SAILED – Left the Tyne June 23, 1904

CONSTRUCTION DETAILS

Swan Hunter Ltd. located an old notebook and provided extracts that included ‘thumbnail’ sketches of the Cl”s hull.

THE BEGINNING AND END OF THE Cl

Information supplied by: Notional Maritime Museum, Greenwich BUILT By – Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson,

Date Built 1903-04

Dimensions – 424’ x 67.6’ x +25’; 12,000 dwt

Alteration – Reduced from four cranes to two in the late ‘50s and remained in this condition until sold.

Sold To – Fran Rijsdijk – Holland NV.

Departed Portsmouth January 15, 1964

Destination – Towed to Hendrik Ido Ambacht, Netherlands and broken up

Article and Photographs by David Maber