Vanishing Spithead Seamarks – by David Maber and Joan Russell

Every day hundreds of motorists drive along Clayhall Road near Stokes Bay, Gosport, and pass over the site of one of Alverstoke’s most famous landmarks (Seamarks) without being aware of its one-time existence. Nor do they ponder the part it has played in saving so many sailing ships from foundering on the treacherous banks and bars of the Solent.

Solentside Gilkicker Point takes its name from a pair of distinctive stone and brick-built towers, called Gilkicker and Kickergill, erected as navigation aids to guide sailing ships through the deep water channels of Spithead as they headed into and out of Portsmouth Harbour. The seaward Gilkicker stood, not on the site of the now derelict Fort Gilkicker, but nearby where the building of Fort Monckton in 1779 caused its demolition. A smaller feature constructed on the newly built Fort Monckton replaced the felled Gilkicker tower, so allowing the navigation facility used by ships’ commanders and pilots to continue.

Kickergill the landward seamark, continued to stand on the edge of a field near Alverstoke Creek until 1965. It was in that year Gosport Borough Council sent workmen to knock it down “to make way for road widening,” It was not scheduled as an ancient monument, it was not even listed as being of historical or architectural interest. So down it came.

Mrs, Jean Hill, an Alverstoke resident, was eyewitness to the destruction of the Kickergill tower in 1965. She has written that:

‘Work began on Monday, June 21, 1965. We were told the estimated time needed to do the job was – ONE DAY! The drills started up and worked relentlessly, the sound intruding into everyday activities. Each succeeding day we walked by to observe progress. By Friday midday there was a gaping hole at the base, clearly this faithful friend could not last much longer.

On Saturday, surely, its hours were numbered. Lunch at home was served in relays with one of us appointed runner for up to the minute reports. Half way through lunch my six-year-old son. dashed in and frantically panted “its going any minute they’ve almost cut through.” We rushed to our favourite landmark to find it still standing. But, after a wait of 20 minutes it fell — so gracefully. The mysterious Kickergill shattered on the ground amid a cloud of dust. We had lost a friend. But why? I asked myself. Surely not because it was considered unsafe!’

Most adults were flabbergasted to see the demolition taking place. But the children were quite excited by it all. Suddenly, where an old familiar landmark used to catch everyone’s eye, there was an empty space, a nothingness.

Twenty of the Council’s pneumatic drill bits were blunted as workers had attacked the tower’s masonry. When the dust cleared stone was sold off to anyone asking for it. It is certain that fragments of Kickergill are, even now, incorporated in garden walls and fire surrounds in the Alverstoke area.

Mrs. Joan Russell, a local historian, offered a prize in 1987 to anyone who could throw light on the derivation of the names ‘Gilkicker’ and ‘Kickergill’. She had long wondered if they were personal names or even naval slang. No one came forward to claim that prize. It was this by-gone challenge that whetted the authors’ curiosity, but it was soon found a ‘name source’ was not the only unanswered question related to the seamarks. It was evident, after browsing through a number of history books, a vagueness existed as to when the towers were built and precisely how they were used by ship’s commanders and pilots.

Seeking answers to all three questions has led the authors to libraries and record offices scouring biographies, histories. pamphlets, dictionaries, maritime charts and naval records.

Firstly, derivation of the Alverstoke tower names. No prior explanation for the names Gill Kicker and Kicker Gill — the original spelling for these towers — was found.

Consider Kicker Gill, a name most likely used to identify the construction contract with its ‘partner’ tower a reversal of the two words. The authors’ submission is that Kicker is a civil engineering term that refers to the stub of a column usually formed at the same time as the foundation slab, it provides the shape and location for the next stage of construction of that column. The tower’s foundation pad would likely have been constructed as a grillage of timbers surrounded with concrete. If formwork was constructed on top of the slab and concrete poured to raise the below-ground part of the column that section would correctly have been termed a ‘Kicker’.

Gill is referred to in Chambers English Dictionary as ‘a small ravine, a wooded glen, a brook. (Old Norse = Gil)’. The tower was in fact located a few metres from the river Alver, now piped, and on a thickly wooded slope photographic records show existed up to the 1930s.

The next task to ascertain when the towers were built involved fruitless visits and wasted days interspersed with an occasional triumph, then, at last, the jigsaw puzz.le began to come together. The sequence of revelations was as follows:

Henry Slight in his ‘Chronicle History of Portsmouth’ (1835) quotes an original inscription that was fixed to the Gilkicker (Gill Kicker) tower and destroyed with it prior to the building of Fort Monckion in 1779.

‘THIS SEA MARK WAS ERECTED BY ROBERT. EARL OF WARWICK, ADMIRAL OF THE SEAS, CAPTAIN RICHARD BI.ITH SEN.. HIS CAPTAIN IN THE PRINCE ROYAL, AND E. COOKE. MASTER OF ATTENDANT, HIS MASTER.’

A variety of authoritative sources offered conflicting construction dates for the Gilkicker tower. Most often quoted was 1669, Clowes The Royal Navy Vol. II gives construction as 1694. Other sources refer to “middle of the 17th century’.Surety, a clue had to be found in the inscription?

Robert. Earl of Warwick, Admiral of the seas was traced and found to be Robert Rich, Earl of Warwick I587-I658. This, quite obviously, determined the date of construction to be before 1658. Who was ‘Captain Richard Blith Senior, Captain of the PRINCE ROYAL? He was found in ‘The Navy in the Civil War’ by J. R. Powell. In 1642 Captain Blith is recorded as commander of the wooden warship VANGUARD. The VANGUARD is shown as being included in a fleet of ships under the overall command of Robert, Earl of Warwick, whose flagship that year was the James. Then, in the fleet of 1643, Blith Senior appears as Captain of the Prince Royal and commanding that same ship was none other than Robert, Earl of Warwick. The following year saw both men serving on the same ship but it was the JAMES and never again was either to serve aboard the PRINCE ROYAL,

So there we have it. There was only one year in history when Robert, Earl of Warwick could have referred to his ‘Captain of the PRINCE ROYAL’ as he had done on the plaque secured to the Gilkicker tower and that was the year he celebrated completion of the two towers. Gilkicker and Kickergill. The year was 1643.

The third and final question to be addressed was, how did the navigation towers figure in securing the safety of cumbersome wind powered wooden ships coming and going in Spithead and the Solent?

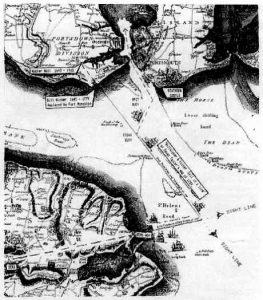

Gosport library held most of the answers in the shape of two maps, they are: (1) Isaac Taylor’s map of 1759 and (2) S. H. Grimm’s map of 1776 prepared in advance of the completion of Fort Monckton.

An extract from the latter is reproduced here. It includes information from Taylor’s map in addition to explanatory notes. The map shows two further navigation towers on the Isle of Wight referred to by Isaac Taylor as Semi and Semi-Not. Without dwelling too long on derivation of these names, the author suggests ‘Semi’ was adapted from Semaphore, as a semaphore station was located near to the Ashey Down Seamark permitting exchange of signals between the Portsmouth Harbour authority and the fleet at anchor off St, Helens. The Semi, as its surviving date plaque still shows, was built in 1735, almost 100 years later than the Alverstoke towers, determining they were not part of the Earl of Warwick’s scheme. A skyline windmill on Ashey Down and a church tower in St. Helens served as Seamarks in his era.

Study of some 16th century British and Dutch maritime maps of the Solent area revealed the inclusion of coastal spires and towers, clearly marked to assist with navigation at sea. Maps of the Solent as early as 1600 show lines extending through pairs of land features offering ship’s commanders guidance around underwater obstructions. Kicker Gill and Gill Kicker appear to be the earliest pair of local purpose-built lowers. The map shows how the towers’ constructor ensured wooden ships a safe passage into and out of Portsmouth Harbour. English Naval ships would lay off St. Helens, in the Iee of the Isle of Wight, waiting a visual signal to proceed to Portsmouth harbour. This signal would be influenced by such matters as favourable winds, tides and other shipping movements.

When under way and in order to gain access to the ‘deeps’ of Spithead, avoiding the shallows and shoals, it was necessary for them to proceed in an easterly direction. Guidance for this manoeuvre was provided for by lining up with the Ashey Down Windmill and St. Helen’s Church tower and later, the seamarks Semi and Semi-Not. With these seamarks lined up astern a ship’s commander or pilot maintained course until his ship was turned to line up with Gilkicker and Kickergill, towers.

A change of course north-westwards was pursued with Gilkicker and Kickergill in line ahead. The contrasting bars of dark brick and light stone on the 60 foot high lower faces made them very conspicuous from the sea. The ship would continue its course in line with the towers until it reached ‘Edgar Buoy’, it was then to set course for Southsea Castle to round ‘Buoy Spit’. Henry Slight’s Chronicled History of Portsmouth makes reference to towers on Southsea Common, in all probability additional seamarks. At the time he wrote in 1835 these seamarks had likely been replaced with sighting poles.

On rounding ‘Buoy Spit’ the Round Tower offered a forward sighting to bring the ship to the Portsmouth harbour entrance The Greenville Collins map of 1692 lays down a less tortuous course for ships headed for Portsmouth harbour by coupling foreground features with background chalkpits on Portsdown Hill.

What of modern times? Pilots still use seamarks. Kicker Gill’s usefulness extended to the day it was felled in 1965. Extract of guidance to Pilots in the Admiralty Manual of Navigation includes a typical navigational manoeuvre for a ship leaving Portsmouth in 1960 ‘Set course with Kickergill Tower through Fort Monckion astern 314°.’

Robert Rich, Earl of Warwick, the Lord High Admiral, had good reason to concentrate on providing extra navigational aids for his navy. In 1643, during the English Civil War, the very year the Gill Kicker and Kicker Gill seamarks were constructed, three of his Parliamentarian ships ran aground on a falling tide and were lost as they attempted to wrest the City of Exeter from Royalist control.

While loss of a ship through grounding would have caused an Admiral acute embarrassment. ‘At the time of the Mary Rose’ published by the Mary Rose Society, reminds us ‘that a pilot hazarding his ship should lose his right hand and his left eye.” Another dire message spells out; ‘If a ship is lost by default of the pilot the mariners may, if they please, bring the pilot to the Windlass, or any other place and cut off his head without the mariners being bound to answer before any judge because the pilot has committed high treason against his undertaking of the pilotage And this is the judgement.’ Bearing in mind recent human navigational errors at sea have resulted in both the loss of ships AND disastrous damage to the world’s ecosystems, perhaps this would be a fitting notice to display on the bridges of today’s fully laden oil tankers!

By David Maber and Joan Russell